One of the most unique places in all of northwestern Iowa is the confluence of Waterman Creek and the Little Sioux River in the southeastern corner of O’Brien County. The steep riparian valleys associated with these watersheds are unusual in the prairie pothole region of Iowa, but these land formations do result from the same glacial forces that created the lakes and marshes of this area.

One of the most unique places in all of northwestern Iowa is the confluence of Waterman Creek and the Little Sioux River in the southeastern corner of O’Brien County. The steep riparian valleys associated with these watersheds are unusual in the prairie pothole region of Iowa, but these land formations do result from the same glacial forces that created the lakes and marshes of this area.

The last glacier affecting Iowa about 12,000 years ago changed the flow of the Little Sioux River. Prior to that it flowed east as part of the Mississippi River watershed, but after the glacier it was diverted to the west and became part of the Missouri River system.

As the glacier retreated, an ice dam broke releasing water from a huge lake that had formed where the town of Spencer is today. The rushing water cut a new channel, steep and scenic, south and west to present day Peterson, Cherokee, and Smithland, where the new Little Sioux River connected with the Missouri River floodplain.

Today, the riverside habitats where Clay, O’Brien, Cherokee, and Buena Vista counties come together are associated with the Little Sioux River and Waterman Creek, plus many smaller watersheds draining into them like Henry Creek and Dog Creek. These draws, ravines, and valleys create attractive habitat for birds, and a number of parks and public areas provide good access.

Wanata State Park (Figure 1.1) across the river from the town of Peterson in Clay County is a large tract of wooded river bottom containing many large black walnut trees. The habitat attracts a number of species not expected in northwestern Iowa including Cerulean Warbler, Pileated Woodpecker, Red-shouldered Hawk, Scarlet Tanager, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, and Kentucky Warbler.

A couple of miles south of Wanata is Buena Vista County Park (Figure 1.2), which displays excellent oak savannah habitat as the prairie meets the woodland edges. I remember experiencing a flight of Swainson’s Hawks so large over this area that I resorted to lying back on a picnic table to save my aching neck while watching them.

In Cherokee County, the Martin Access Area (Figure 1.3) is a county park along the river with wooded ridges and valleys that attract bird life. This park also has two large stands of mixed conifer trees. These pine groves can be counted on to harbor good birds, especially in winter when the road is closed, and it takes a pretty good hike to get to them and check them out. Both crossbill species, Barred Owl, and Northern Goshawk like these pine microcosms.

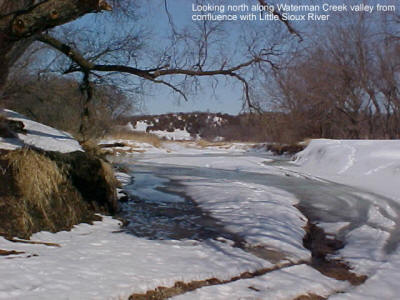

Waterman Prairie (Figure 1.4) is in Waterman Township in the very southeastern corner of O’Brien County. This township has the most land in public ownership due to the substantial watershed and valley of Waterman Creek intersecting with the even larger Little Sioux River valley. This creates a confluence of the two waterways that maintains open water through the coldest winters. Eagles and humans and all manner of living creatures are attracted there. It occupies a place of natural power.

From the point where it intersects the Little Sioux River, the Waterman Creek bed and valley are now under public ownership. There is protection for a full 1.5 miles north thanks to a recent acquisition by the Nature Conservancy. This unique riparian habitat will be managed for the benefit of birds and other wildlife, and will provide enjoyment to humans who value rich and interesting natural environments.

From the point where it intersects the Little Sioux River, the Waterman Creek bed and valley are now under public ownership. There is protection for a full 1.5 miles north thanks to a recent acquisition by the Nature Conservancy. This unique riparian habitat will be managed for the benefit of birds and other wildlife, and will provide enjoyment to humans who value rich and interesting natural environments.

Down river from the confluence, major tracts of native prairie have been preserved and grasslands restored as part of the Waterman Complex (Figure 1.5).

The one significant body of water in the area is the human-made lake at Dog Creek County Park (Figure 1.6). Associated habitat has been known to attract Bell’s Vireo.

Native oak savannah prairies are still found in many places on the steep hillsides that line the watersheds throughout the area. Too steep to be tilled or cropped, and steep enough even to be free from heavy grazing pressure, these grasslands survived the onslaught of mechanized agriculture that decimated other tall grass prairie habitat.

Suppression of fire on these valleys by humans did change natural events, however. Originally, the prairie fires were started by lightning and also promulgated by Native Americans. Left behind were hills of prairie grass interspersed with burr oak trees, which were about the only woody plant species that could consistently survive the periodic prairie fire events. Eastern red cedar trees also were native to the area, but they would have survived only in the draws and other protected areas. The fires killed the cedars in open areas and early settlers called them “prairie candles.”

Now that fire has been absent for over a hundred years, red cedars have grown out of the valleys to cover many of the hillsides. Although bad for the native grasses, this has been good for the birds, especially the winter birds. The cedars provide shelter and food in the form of berries. Waterman Creek runs fast and is spring fed, which keeps open water year around. These three vital ingredients allow many different birds to survive harsh northwestern Iowa winters.

Now that fire has been absent for over a hundred years, red cedars have grown out of the valleys to cover many of the hillsides. Although bad for the native grasses, this has been good for the birds, especially the winter birds. The cedars provide shelter and food in the form of berries. Waterman Creek runs fast and is spring fed, which keeps open water year around. These three vital ingredients allow many different birds to survive harsh northwestern Iowa winters.

Throughout the winter, this area harbors American Robin, Cedar Waxwing, Eastern Bluebird, Purple Finch, and Northern Flicker. As you might expect, an area attractive to these species also holds the potential to attract the rarer cousins in these bird families.

Bohemian Waxwings have been found hanging out among the flocks of Cedar Waxwings. Mountain Bluebirds also have been seen cavorting with Eastern Bluebirds, and in one case in the spring of 2000, a male Mountain Bluebird tried to pair with a female Eastern Bluebird in this area. Townsend’s Solitaires apparently find the area reminiscent of the juniper canyons of the west where they reside. They have been found regularly in the Waterman area in the fall and winter as they wander east exercising their vagrant tendencies.

When there is an abundance of smaller birds in such habitat, accipiters also are attracted. Both Sharp-shinned Hawks and Cooper’s Hawks hunt the area and Cooper’s Hawks have been found nesting. Bruce Morrison, who has lived on an acreage along Waterman Creek for only a couple of years, has had Northern Goshawks on two separate occasions hunting winter birds attracted to the feeders in his yard.

When there is an abundance of smaller birds in such habitat, accipiters also are attracted. Both Sharp-shinned Hawks and Cooper’s Hawks hunt the area and Cooper’s Hawks have been found nesting. Bruce Morrison, who has lived on an acreage along Waterman Creek for only a couple of years, has had Northern Goshawks on two separate occasions hunting winter birds attracted to the feeders in his yard.

The ridges and valleys of the area attract migrating raptors and hold them through the winter. A fall hawk watch, held on a single day in late September over the past six years, has produced good numbers and a variety of hawks, falcons, and eagles. More thorough and consistent survey work through the fall season such as that occurring at the Hitchcock Nature Area hawk watch site could provide very interesting results.

In January 2004, Darwin Koenig and I were running an eagle survey along the Little Sioux River. In addition to the dozen Bald Eagles we expected to see, we found two Golden Eagles. The first, an immature, was shooting through draws and skimming along ridges of the river valley. It would extend its talons and grab at sticks on the ground like they were prey. It would then flare up in the air, drop the inanimate object and repeat the game once again. The bird seemed to be practicing its hunting skills.

The second Golden Eagle was a beautiful adult sitting in an open field. It flew up and along Waterman Creek and soared away over the opposite ridge. Based on sightings over the past five years, these valleys and this area would appear to draw and hold Golden Eagles through the winter months and be a consistent winter location for them in the state.

Rough-legged Hawks in winter, Red-shouldered Hawks occasionally in summer, both Broad-winged Hawk and Swainson’s Hawk flights in migration, and all of the subspecies of Red-tailed Hawk are drawn to the area. The valleys of Waterman Creek and the Little Sioux are host to buteos in abundance.

Falcons, too, hunt the area. Not only are Peregrine Falcons seen in migration, but Merlin and Prairie Falcon have shown up in this winter wonderland for raptors. The Gyrfalcon found injured in March 2001 in rural O’Brien County was suspected in two earlier sightings from the Waterman area that were unable to be confirmed.

In 2005, the O’Brien County Conservation Board anticipates breaking ground for the Prairie Heritage Nature Center. This facility will be located on 40 acres of native prairie on a hillside facing northwest near the confluence of Waterman Creek and the Little Sioux River. The location is one mile north off Highway 10 at the end of Yellow Avenue and incorporates the Hannibal-Waterman Area (Figure 1.7)

In 2005, the O’Brien County Conservation Board anticipates breaking ground for the Prairie Heritage Nature Center. This facility will be located on 40 acres of native prairie on a hillside facing northwest near the confluence of Waterman Creek and the Little Sioux River. The location is one mile north off Highway 10 at the end of Yellow Avenue and incorporates the Hannibal-Waterman Area (Figure 1.7)

It will offer a commanding view to the north up the valley of Waterman Creek. The Little Sioux River flows from the east and wraps its scenic valley around the hillside as it captures the current from Waterman Creek and then curves south toward Cherokee County. A facility at that location will be a boon to birders and nature lovers.

The habitats associated with Waterman Creek and the surrounding Little Sioux River valley are good for birds and thereby attractive to birders. I invite you to put this destination on your short list of birding hotspots in Iowa and I hope someday to see you there.